Technology in the Classroom

CLASSROOM INFRASTRUCTURE

(The following is an abstract from “Games for a Digital Age”)

OVERVIEW

In the past, schools were not receptive to technological innovation because many lacked the basic technology infrastructure. This lack of resources blocked any attempt to base curriculum on digital resources, including games or simulations. In our judgment, this picture is changing dramatically. Together, these changes comprise a technology-driven disruption. This is a time of change in the classroom. As noted by Vic Vuchic, Associate Program Officer at the Hewlett Foundation.

In the past, schools were not receptive to technological innovation because many lacked the basic technology infrastructure. This lack of resources blocked any attempt to base curriculum on digital resources, including games or simulations. In our judgment, this picture is changing dramatically. Together, these changes comprise a technology-driven disruption. This is a time of change in the classroom. As noted by Vic Vuchic, Associate Program Officer at the Hewlett Foundation.

The buzz driving the VC community may be because the infrastructure is possibly maturing to a level where you can do distribution and reach at a reasonable cost. There may be enough districts structure that it takes a lot less capital to have a fair impact. But the majority of schools they visit still have horrific infrastructures.

Using Web 2.0 social tools in the classroom allows for students and teachers to work collaboratively, discuss ideas, and promote information. Blogs, wikis, and social networking skills are significantly useful in the classroom. After initial instruction on using the tools, students also reported an increase in knowledge and comfort level for using Web 2.0 tools.

MOVING TO ONE-TO-ONE

One-to-one classrooms where every student has a computer have become increasingly common in U.S. schools. This trend has accelerated in the past four years, abetted by a price drop for all devices and the increasing popularity of tablets and mobile devices in schools.

and the increasing popularity of tablets and mobile devices in schools.

One-to-one computing is ubiquitous throughout higher education where almost all students now carry around multiple devices. Today, K-12 is finally embracing this goal of one-to-one due to the increasing acceptance of digital curricula, the need to prepare students for 21st century skills in a digital world, and the encouraging research results of one-to-one initiatives.

THE RISE OF “BYOD”

“Bring Your Own Device” (BYOD) involves students bringing their own cell phones, tablets, and laptops into the classroom for use in educational activities and real-time assessments. BYOD is being embraced by schools throughout the country as a way of achieving one-to-one initiatives. This tactic is a natural solution for schools seeking to meet the challenges of the move to digital curricula and to move forward on the goals contained in the National Education Technology Plan.

Seventy-seven percent of children ages 12 to 17 own cell phones, and about a third of these are smart phones that have many of the same capabilities as laptops. Even kindergarten students now have access to mobile devices. As such, the BYOD movement could have a dramatic and compelling effect on how student-computer ratios are measured and understood.

The impact on the market for software and digital content and resources could also be significant. The resulting increase in access and cost-savings should increase demand and provide resources for applications. At the same time, the likely diversity of devices in a given classroom or school may have a great impact on developers who will need to ensure some degree of standardization of display, navigation across platforms, screen sizes, and operating systems.

The impact on the market for software and digital content and resources could also be significant. The resulting increase in access and cost-savings should increase demand and provide resources for applications. At the same time, the likely diversity of devices in a given classroom or school may have a great impact on developers who will need to ensure some degree of standardization of display, navigation across platforms, screen sizes, and operating systems.

However, the BYOD trend may have lopsided effects on hardware and software spending from district to district, and issues such as security, privacy, the digital divide, and adequate teacher professional development will need to be addressed for BYOD to gain ground quickly. Further, more focused research is needed to shed light on the real nature of educational software and platform use by older students, who may be more likely to take advantage of free online and mobile services, resources, software, and business-to-consumer products on their own (or their parents’) initiative.

The related possibility of one-to-one classrooms on a larger, district-wide scale could also affect how vendors—content vendors especially— approach their digital offerings. At the moment, many content publishers are not fully up to speed in offering useful formats and easy interfaces for their products across multiple devices; the incentives to do so will change as standards begin to emerge and demand and competition grow.

INTERACTIVE WHITE BOARDS

The incredibly rapid and widespread acceptance, purchase, and installation of interactive whiteboards in the education community have almost no precedent. In a recent survey of technology leaders, interactive white boards were identified as the most useful classroom tool. A 2011 report said that more than 63% of teachers have their own interactive white board, and another 7% share one with one or two other teachers.

interactive white boards were identified as the most useful classroom tool. A 2011 report said that more than 63% of teachers have their own interactive white board, and another 7% share one with one or two other teachers.

The interactive whiteboard market continues to increase, growing by 15% in 2011 for total revenues of $1.4 billion, and it is predicted to grow more than three-fold over the next 5 years. Even in the current economy, digital sales of interactive white boards, online digital content, LMS/SIS, and mobile devices are up, and print sales are down.

INTERNET ACCESS

The U.S. Department of Education reports that as of 2008, effectively all public school computers were connected to the Internet and the current student to computer ratio is less than 3:1. The move towards universal connectivity is largely due to the E-Rate program. Across the board, connectivity is continuing to improve, although gaps in support and technology infrastructure continue to plague schools.

The U.S. Department of Education reports that as of 2008, effectively all public school computers were connected to the Internet and the current student to computer ratio is less than 3:1. The move towards universal connectivity is largely due to the E-Rate program. Across the board, connectivity is continuing to improve, although gaps in support and technology infrastructure continue to plague schools.

Although nearly every school has Internet access, classrooms frequently are not connected or the connections are super slow. The hurdle is limited capacity inside schools to transmit data, or bandwidth. Today, about 80 percent of schools have Internet capabilities that are too slow or isolated to places like front offices and computer labs. Many schools have the same amount of connectivity as an average home. That means several hundred kids or more operate on an Internet connection similar to that used in a house by four family members.

In some districts, particularly rural ones, cost is a huge factor in getting access to lines that would bring broadband into schools. To buy the equipment and install Wi-Fi costs an estimated $30,000 to $50,000 per school and to run fiber optics into the school can cost tens of thousands more per mile. Broadband would cost about $9,000 a month without a special Federal Communications Commission program that reduces it to $2,000 to $3,000 a month.

Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates have contributed a combined $9 million to the nonprofit EducationSuperHighway, a San Francisco-based nonprofit organization working to improve connectivity in schools through Zuckerberg’s Startup: Education and Gates’ foundation.

Overall trends in the hardware and software industries have an important influence on the direction of technology purchases by K-12 institutions. Several notable developments affecting education include:

• Cloud-based services: The growth and expansion of storage and resources, virtualization tools, and improved Internet access have made it easier for companies to offer key software products and services online. In turn, this trend has lowered costs for implementation and training on new software for schools and educators.

• Mobile technologies: A flourishing ecosystem of third-party developers who supply useful applications has sparked interest in educational applications for mobile devices. Although mobile  technology was not a main focus of institutional spending in 2009-2010, a new pool of entrepreneurs and established companies (e.g., Apple and Nokia) have been paying increased attention to potential K-12 institutional markets for their products and apps.

technology was not a main focus of institutional spending in 2009-2010, a new pool of entrepreneurs and established companies (e.g., Apple and Nokia) have been paying increased attention to potential K-12 institutional markets for their products and apps.

• Cheap data storage: Whether they are tied to cloud-based services or on-site servers, data storage and management systems have continued to become more scalable and cost-effective, both of which are key elements for schools. Available data storage is also important for vendors, as educational products become increasingly sophisticated in tracking incredibly fine-grained student-, educator-, school-, and district-level information (Johnson, Smith, Levine & Haywood, 2010).

• Social networks and community websites: The increasing acceptance, use, and consumer understanding of collaboration technologies and platforms for educators and students to share ideas, resources, reviews, and information on an up-to-the second basis has led to these resources being co-opted for educational purposes.

PLATFORM COMPATIBILITY

Increases in BYOD initiatives and the use of interactive whiteboards, tablets, mobile devices, and laptops in the K-12 school setting is forcing both schools and technology developers to support mixed device environments. The issue with this is that each tool enters the market bundled with a different level of software and cross-platform compatibility, and providing even forward/backward compatibility within a platform can present significant challenges.

Schools must ensure that their wireless infrastructures have enough bandwidth and that their device management capability is sufficient to handle the increased demand from multiple devices. School administrators must be aware that they might buy new technologies that are not able to communicate or connect with each other or with other components that already exist in the school infrastructure. In turn, developers must ensure that their products can run on multiple platforms and be hosted in multiple infrastructure environments. To do so, developers are often required to create and maintain different versions of a game or simulation for each major platform type.

Despite progress being made in universal design and interoperability standards, producing cross-platform products is expensive and often involves different development teams for each major platform type. Thankfully, such issues are likely to be resolved in the next few years, lowering the cost burden of making products available to multiple devices and browsers.

Digital On-Line Teaching and Learning Platforms

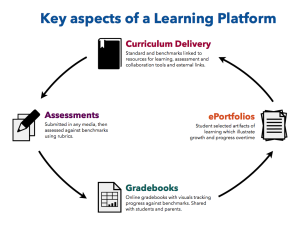

Digital curricula are designed for networked classrooms where every student has a computing device. i.pel’s integrated digital curriculum will be delivered by on-line teaching and learning platforms which will be designed to operate in one-to-one classrooms, deliver a personalized curriculum to students, and provide support for the teacher to manage all classroom activities. They will contain open-ended explorations, practice environments, games, videos and other digital learning objects.

The On-line School

In fully online public and private schools, students will complete all coursework online. Instruction will be facilitated by a parent or guardian with the assistance of a state-certified teacher. Teacher interaction will be accomplished through virtual classroom environments, telephone, and face-to-face meetings. In hybrid schools, students will complete the same curriculum but attend a physical school with other students and teachers.

As with all i.pel programs courses will be able to be taken either at the students school or online. Students will be able to attend live online classes and have more communication with teachers, via e-mail, phone, and online conferences.

In K to K8 the instructor will spend approximately 3–5 hours each day taking attendance, monitoring students’ progress, and helping students with their lessons. As grade level increase, instructor’s face-time will be reduced and students will be able to work more on their own. In K-9 to K-12 students will manage his or her own schedule and have more interaction with other students as instructors’ transition to a support role from direct instruction.

ARTICLES

LEGISLATORS CALL FOR IMPROVED SCHOOL, LIBRARY INTERNET

By Glenda Anderson

The Press Democrat 12/31/2013

Rep. Jared Huffman, D-San Rafael is among members of Congress pushing FCC to modernize services. More than two dozen members of Congress have signed a letter calling for upgrades to a federal program that subsidizes Internet access at schools and libraries. “The program hasn’t kept pace with changing technology,” Huffman said in a statement.

Most schools currently have Internet access but their connections are too slow to accommodate the latest in computerized educational tools, according to the letter sent to the Federal  Communications Commission. The commission, which oversees the E-rate program, agrees it should be updated to provide faster Internet service. In July, FCC officials announced plans to review and modernize the program, which has been in operation since 1997. It was unclear Monday how much the proposed upgrades would cost. FCC officials said that’s one aspect of the program they are studying.

Communications Commission. The commission, which oversees the E-rate program, agrees it should be updated to provide faster Internet service. In July, FCC officials announced plans to review and modernize the program, which has been in operation since 1997. It was unclear Monday how much the proposed upgrades would cost. FCC officials said that’s one aspect of the program they are studying.

The program currently costs $2.3 billion annually. The costs are borne primarily by customers of telecommunication companies that provide interstate or international services. It’s one of four programs funded through the Universal Service fees customers are charged on their monthly bills. Altogether, the four programs add up to about $8.5 billion annually, according to the FCC.

Universal Service fees have more than doubled over the last decade to about 15 percent, according to the New York Times. Other programs funded though Universal Service fees include telecommunications subsidies to low-income residents, rural health centers and rural areas in general.

Critics have said the fees that support the E-rate program are hidden taxes. Supporters say the program is crucial to students’ success in school and their futures in a competitive job market and world. “Adequate broadband is an equity issue that must be achieved to ensure that all students, rural, remote and urban, have the opportunity to receive a quality education to graduate from high school college- and career- ready,” said Mendocino County Office of Education Superintendent Paul Tichinin.

The program provides subsidies of between 20 percent and 90 percent to eligible recipients. The larger subsidies go to schools and libraries that are rural and have high poverty rates, according to the FCC.

BROADBAND BACKUP: SCHOOLS STRUGGLE TO STAY CONNECTED

By Kimberly Hefling

Associated Press 12/5/2013

80% of facilities said to lack adequate Web access; Gates, Zuckerberg donate $9M to effort

Needed to keep a school building running these days: Water, electricity — and broadband. Interactive digital learning on laptops and tablets is replacing traditional textbooks in many cases. Students are taking computer-based tests instead of fill-in-the-bubble exams. Teachers are accessing far-off resources for lessons.

Technology is changing the way students are taught — and tested. But there’s a catch — most of it is occurring in schools that have rich connectivity to the Internet. Although nearly every school has Internet access, classrooms frequently are not connected or the connections are super slow. The hurdle is limited capacity inside schools to transmit data, or bandwidth. “It’s the backbone. We have to actually think not just about the sustainability of the current traffic, we’re talking about exploding traffic,” said Raj Adusumilli, assistant superintendent for information services in the Arlington Public Schools in northern Virginia.

The effort to get high-speed Internet access in every school got a boost Wednesday from the philanthropy of two technology gurus — Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates. Zuckerberg’s Startup: Education and Gates’ foundation have contributed a combined $9 million to the nonprofit EducationSuperHighway, a San Francisco-based nonprofit organization working to improve connectivity in schools. “When schools and teachers have access to reliable Internet connections, students can discover new skills and ideas beyond the classroom,” Zuckerberg said in a statement. The funds are expected to be used to provide technical expertise to schools and use competition to help drive costs down. It likely would cost billions to get highspeed Internet access to every school in America.

President Barack Obama this past summer set a goal of having 99 percent of students connected to high-speed Internet connections within five years. Also, the Federal Communications Commission is weighing changes to a program to increase connectivity in schools. Today, about 80 percent of schools have Internet capabilities that are too slow or isolated to places like front offices and computer labs, said Richard Culatta, director of education technology at the Education Department. Many schools have the same amount of connectivity as an average home. That means several hundred kids or more operate on an Internet connection similar to that used in a house by four family members. That leads to networks that are slow and prone to crashing.

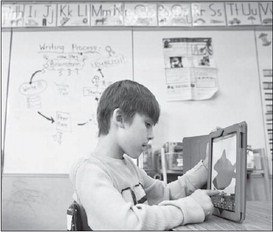

“There are many examples of fantastic things happening across the country, but they are happening in places where infrastructure is in place that supports these types of innovations,” Culatta said. At Jamestown Elementary School in Arlington, Va., first and second-graders use iPads to document the growth of caterpillars for a science project or record themselves reading out loud as they make electronic books. “It’s fun. You can draw and make books and movies,” said 7-year-old Braeden Meeker. “We learn writing and math. We learn a lot of things.” But one day in class, the system crashed when students tried to look up their house on a Google map.

“There are many examples of fantastic things happening across the country, but they are happening in places where infrastructure is in place that supports these types of innovations,” Culatta said. At Jamestown Elementary School in Arlington, Va., first and second-graders use iPads to document the growth of caterpillars for a science project or record themselves reading out loud as they make electronic books. “It’s fun. You can draw and make books and movies,” said 7-year-old Braeden Meeker. “We learn writing and math. We learn a lot of things.” But one day in class, the system crashed when students tried to look up their house on a Google map.

The district has upgraded to high-speed broadband, or Internet access that is always available and faster than dialup, in middle and high schools and is in the process of doing the same in elementary schools. The goal is to assign a device to each student by 2017. In some districts, particularly rural ones, cost is a huge factor in getting access to lines that would bring broadband into schools. To buy the equipment and install Wi-Fi costs an estimated $30,000 to $50,000 per school and to run fiber optics into the school can cost tens of thousands more per mile, said Evan Marwell, CEO of EducationSuperHighway.

A lack of competition for broadband access helps drive up costs at Chautauqua County Unified Schools, a district with about 360 students in an agriculture and oil community in rural Kansas. About three-quarters of students in the district qualify for free or reduced lunches. The district relies on distance learning to teach Spanish, physics and calculus and has issued an iPad to all students in upper grades, said Nancy Pinard, the district’s technology director. Its broadband bill would be about $9,000 a month without a special Federal Communications Commission program that reduces it to $2,000 to $3,000 a month.

“My big thing is the cost of it,” Pinard said. “How long will we be able to maintain where we are at just because of the cost.” The drive for increased broadband capabilities has been fueled in part by a drop in the price of tablets and their rising popularity, said Doug Levin, executive director of the State Educational Technology Directors Association.

L.A. SCHOOLS PAYING $768 PER STUDENT FOR IPADS

LOS ANGELES 1/2/2014

The Los Angeles Unified School District spends more to equip students with tablet computers than other school districts, which choose less expensive devices, according to a report.

LAUSD is paying $768 apiece for an iPad for its students, teachers and administrators. Meanwhile, the Perris Union High School District spends $344 for a Chromebook for each student, while Riverside Unified opts for cheaper devices like the Kindle Fire and iPad Mini, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Across the nation, schools are embracing technology and increasingly providing students with tablets in the hopes that they will become more engaged in learning. At the same time, schools are trying to hold down costs by buying cheaper models or leasing them.

Not only did LAUSD choose a higher-end Apple iPad, but the district also paid to have new math and English curriculum pre-loaded on the tablets. Schools Superintendent John Deasy defended the decision. “Our youth deserve the best we can afford.”

THREE STUDENT SUCCESSES WITH IPADS

By Anya Kamenetz

Hechinger Report October 24, 2013

The last time I wrote about iPads in the classroom, it was about a school district doing almost everything wrong. Today I talked to a teacher in the Chicago Public Schools who has a 180 degree view.

When the iPad first came out in 2010, Jennie Magiera made fun of her friends for buying them: “Nice job–you got a giant iPhone that can’t make phone calls!!” But when a grant bought iPads for her fourth and fifth grade class, the teacher quickly found a path to transforming her teaching and learning practice. While tests are only one measurement of success, she went from having just one student out of 15 “exceed” on state tests in fourth grade, to having 10 “exceed” the next year.

Just three years later she has gone from the classroom to helping other teachers implement one-to-one iPad programs, as the digital learning coordinator of the Academy of Urban School Leadership, a network of 29 public (non-charter) schools that are 90% free and reduced lunch. Her focus is on using technology to make good teachers better, and to let students be the best they can be.

“I could seriously sit here till we both passed out telling stories of powerful things that happen every day,” Magiera says. Here are three of those stories.

1) The Second Grade Experts

The students in Magiera’s network are not “digital natives.” Most of them don’t have access to devices at home because of family income. Nevertheless, they are engaged by and excited about using computers, and because the teachers are learning to use them along with the students, there’s sometimes a role reversal in the learning process.

“We had three girls who came in during recess because it was cold and wanted to help us provision the tablets,” says Magiera, meaning setting them up to run certain kinds of apps. “Right away they started problem-solving: ‘She already hit that button…’ ‘Why don’t you try the green box in the upper left hand corner, since you already did the blue one in the lower right?’” They learned the term “microUSB” and created an organizing system to see which iPads were charged. In this mundane technical activity, Magiera saw the students take on a real problem and work alongside adults in a way that seven-year-olds don’t always get a chance to do.

2) The Shy One Speaks

Magiera had one very intelligent student who was afraid to speak up in class–she tried writing questions down on notecards, and warning him that she was going to call on him, but he would still freeze up. With the iPads she implemented a classroom “backchannel,” allowing students to participate in a text-based chat as part of the class discussion. In that forum, the boy blossomed. “I was not only able to see who was participating but the quantity and quality of their participation,” she says. “And what I found was this young man not only was the most vocal kid, he was the best in the conversation. He was hitting all the markers, responding to other students, coming up with novel ideas, supporting peers in a positive manner, and really thriving and flourishing in a community of thought when he didn’t want to speak up [before].”

3) The Troublemaker Revealed

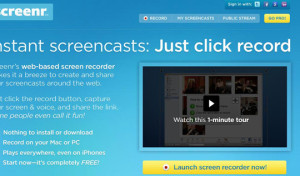

Yet another student, she says, was constantly disruptive. His test scores and other math grades were poor. One day, she started using a technique called “screencasting,” a program where students can draw or write using a stylus and narrate at the same time, producing a video in a similar format to a Khan Academy video (see Screencasting).

“The answer was 15 cents and he wrote $16. I would have thought he wasn’t paying attention or didn’t try. But when I go into his screencast video, it was 60 seconds of the best math I’ve ever seen as a math teacher.” The student had arrived at the wrong answer because of a tiny mistake, but he had devised his own original path through the problem, using his knowledge of fractions to create a system of proportions, a concept he wouldn’t be introduced to for another year or two. “He solved it completely on his own, narrated it beautifully, and had the most amazing thought process.” From watching this one minute of video, Magiera got insights into this student’s math skills that she hadn’t learned from having him in the classroom for over a year.

math teacher.” The student had arrived at the wrong answer because of a tiny mistake, but he had devised his own original path through the problem, using his knowledge of fractions to create a system of proportions, a concept he wouldn’t be introduced to for another year or two. “He solved it completely on his own, narrated it beautifully, and had the most amazing thought process.” From watching this one minute of video, Magiera got insights into this student’s math skills that she hadn’t learned from having him in the classroom for over a year.

But the insights didn’t end there. Magiera then had the student re-watch his own video. She saw his reactions go from defiance (“lady, I already did it for you once, you want me to watch it now?”) to pride (“yeah! I got that!”), to dismay (“Oh my god, I messed that up! I can’t believe it! I was so close,”). And finally he asked her, “Can I do it again?”

“I just about died,” Magiera says. “I was ready to burst into tears. This was a kid you could not get to do homework. Classwork was a struggle. Now he just heard his own thinking, which is really hard for a nine year old to do, and he wanted to improve authentically out of his own motivation. That was a feedback loop we did consistently from then on.”

Recent Comments