K-12 Public Schools

ISSUES OF THE SCHOOLHOUSE AND CAMPUS

According to Simpson, et al. (2011) in their book, The struggle for power and influence in cities and states, public education is a part of the soul of our nation. Teachers in America transmit values about democracy. Knowledge and the capacity to solve problems that we learn in school are the determinants of individual success as well as national economic productivity.

Almost one in four Americans is enrolled in education, from the preschool level through our colleges and universities. As of 2016, there were approximately 59 million students in the K-12 schools (50.1 million attending 98,817 public schools; 2.9 million attending 6,700 charter schools (5.7%); 4.9 million students attending 30,861 private schools; and 1.8 million students being home schooled (see: Keeping Pace with K-12 Online Learning report – 2015) (Kpk12); and 20.5 million in higher education. One in every 25 employed Americans is a public-school employee. (1) Total state and local education spending reached $689 billion in 2016, or about $12,296 per student in the United States, and represented the largest expenditure of state and local governments, at about 30 percent of state and local budgets. (2) Total education revenues have represented about 4 percent of America’s gross domestic product in recent years. (p. 277)

Given the fundamental importance of education, there are intense struggles over who governs these institutions and who pays. The stakes are also immense – the competitiveness, wealth, and global standing of America depend on the skills and intellectual prowess of our citizens. Yet international comparisons of reading, math and science scores consistently find American 15-year-olds ranking 15th to 20th among developed nations, while American expenditures per pupil rank third among nations. (3) While citizens are quite vocal in their demands for better education in return for their tax dollars, it is not clear which policies are most effective in improving education.

The study of how cities and states deal with education is illustrative of other public policy conflicts such as health care, economic development, and public safety. In education as well as these areas, the struggle is not just about power and influence over policy but also about controlling billions of dollars, thousands of jobs, and profitable contracts. These decisions illustrate the pull of representative and participatory democracy. Some decisions are made at the most local level by parents, teachers, and community members through PTA and school council meetings open to the public. As students get older, they have a voice through student government,’ campus organizations, and a student newspaper. But most critical decisions are made by a school bureaucracy headed by school superintendents, elected school boards, and elected and appointed officials in state and federal government.

The institutional structures and political processes determine how education policies get made. And in education, the outcomes matter in a very important and personal way. If a large percentage of students fail to finish high school, or if college students do not have the right skills and knowledge to get good jobs upon graduation, these are factors that affect individual’s life choices and the capacity of our communities and nation to compete effectively in the global economy.

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN PUBLIC EDUCATION

In 1642, the colonial legislature of Massachusetts directed “certain chosen men” to see that “children were being trained in learning and labor and other employments – profitable to the state.” For the first time in the English-speaking world, a public body enacted legislation to require that children be taught to read. Later, the Land Ordinance of 1785, enacted by the Congress under the Articles of Confederation prior to adoption of the U.S. Constitution, declared: “Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools, and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.” To back up this language, the Congress set aside a portion of every township for the support of schools. (4)

In the Northeast, “district” or “common” public primary schools became a model for the nation. Supported by district taxes, state funds, and tuition paid by parents, these schools were (p. 278) open to all. Reformers led by Horace Mann preached that common schools could, if properly run, protect “society against the giant vices . . . against intemperance, avarice, war, slavery, bigotry, and the woes of want.” According to historian David Nasaw, “The campaign for the common schools – through the later 1830s and 1840s – was no more and no less than a campaign for public taxation.” Without taxes specifically earmarked for schools, there could be no common schools. Opponents of taxation for free schooling fought back, yet ultimately the nation became blanketed by public schools. Public education, however, was not extended to everyone. “Schooling for blacks was from the 1830s on, proscribed by law in the South and by ‘custom and popular prejudice’ elsewhere,” Nasaw states. The fines for teaching African Americans, whether free or slave, ranged from $100 in Virginia to six months’ imprisonment in South Carolina? (5)

In 1862, during the tumult of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Morrill Act, which provided for the creation of “land grant” universities. Named for U.S. Representative Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont, the act provided each state 30,000 acres of public land for each senator and representative in that state, with proceeds from the sale of that land to be invested in a perpetual endowment fund to support colleges of agricultural and mechanical arts in the state.(6) Yet even with this strong federal government support for public education, by 1900 only 8 percent of the population 14-17 years of age was enrolled in grades 9 through 12 in public high schools, although some students attended private academies and post-grammar schools. (7)

Ever since Horace Mann and other educators advocated for common schools in America, educational reform has been a continuing theme. In the Progressive Era of the early 20th century, business and civic groups fought to take control of local schools away from urban political machines they believed to be corrupt, inefficient, and ineffective. According to Nasaw, the civic reformers, muckraking newspaper reporters, and business leaders agreed that neighborhood school board members were at fault for overcrowded, understaffed, patronage-rife schools that failed to keep adolescents in school long enough to learn “how to work.” Coming primarily from the elite class of society, the reformers and business leaders focused on state legislative change that would encourage a model of a centralized school board with a superintendent and professional staff. In most major cities, centralization was soon the norm (8) (p. 279).

After World War II, a wave of consolidation closed thousands of one-room schools, whose students were usually then enrolled in township or smaller school districts. Thus, while there were approximately 40,000 public school districts serving the nation in 1960, by 2004 this was reduced to 14,000. (9) At the same time as the number of districts declined, a dramatic growth in spending for public education began. This increased after the Soviet Union beat the United States into space by launching its Sputnik satellite in 1957, startling Americans out of complacency. Consequently, while America had spent on average $1,897 per pupil in 1960, the figure was $3,273 by 1970, $7,814 in 2000 and $12,298 in 2016. All figures are adjusted for inflation to dollars from the year 2000. (10)

WHO GOVERNS OUR SCHOOLS?

Although public schools are primarily creatures of state government, responsibility for the day-to-day operation of public schools rests with local school boards. Nevertheless, as with other aspects of American society, the federal government has considerable influence on American education. Both chambers of the U.S. Congress have committees and subcommittees dealing with education, and there is a Department of Education in our nation’s executive branch. Moreover, the U.S. Supreme Court and lower federal courts have handed down many court decisions dealing with education. One of the most important court decisions of the 20th century was Brown vs. The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), which struck down “separate but equal” as a justification for racial segregation of public schools.

Fourteen states elect a statewide superintendent of education or public instruction. Boards and commissions select a state schools superintendent or commissioner in 25 states. In 11 states the governor appoints the chief state schools officer, generally with the advice and consent of the state senate. (11) These state offices oversee public schools and, to a much lesser extent, private education at the local level.

In many cases, state policy is carried out through school mandates, which are laws or regulations that local school districts must follow. What goes into mandates is determined by diverse government officials and interests, including state legislators, governors, state education departments, teacher unions, and school board associations. With the potential to control almost any aspect of school governance, mandates can set course requirements such as consumer or physical education, the number of days in a school year, or what holidays must be honored.

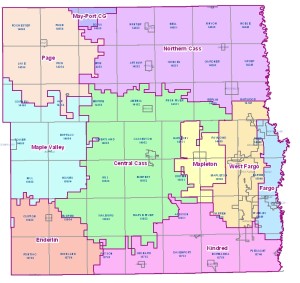

School superintendents complain that these mandates – usually described in the hundreds of pages of a state’s school code – are often unfunded, which requires local school districts to pay for them. While a few states have developed procedures for requesting waivers from such regulations, some interested parties, including the federal government (which has its own indirect mandates) and teacher unions, are vigilant to see that their interests are protected. Thus, while most of the approximately 13,600 school districts in the United States are governed locally by elected school boards and managed by local school superintendents, school districts do not have the flexibility of cities’ home rule powers.

Local control

The concept that school affairs should be governed primarily by the local school district rather than by state and federal government laws and regulations – continues to be the mantra of public secondary and elementary education in many localities. Yet states and the federal government have been seizing more authority over the public education enterprise. Teacher unions have become more aggressive in recent decades. The business community has reasserted its interest in education policy. And charitable donors such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation are trying to reshape schools. Most of the recent policy-making has been spurred by anxiety about the condition of American education (p. 280).

Reform Efforts

In 1975, Americans learned that scores on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) had been declining for 10 years. In 1983, a national commission issued A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform, which documented poor performance and low expectations in the schools. (12) The report aroused significant anxiety among America’s leaders and helped launch a wave of school reform that continues today.

Prior to the 1970s, education-related groups at the state and local level were the primary initiators of education policy. (13) However, from the 1970s on, new groups outside the field of education – including politicians, governors, and prominent business leaders – began to exert influence on the shaping of educational policy that made its way onto the policy agenda in the states. (14)

Thus, the local control model of school governance and finance evolved into a state system of finance, standards, and assessment. In 1960, education professor Myron Lieberman predicted that local control of schools would have to give way to a system of educational controls in which the roles that local communities played would be ceremonial rather than policy-making. According to Lieberman, local control had become “a corpse.” (15) State policy activism grew as state funding of local schools increased. In 1971, states provided 38 percent of local school funding; by 2003, that figure had reached 49 percent of total funding, with the local districts providing 43 percent and the federal government 8 percent. (16)

Since local schools are creatures of their states, the latter have powerful statutory tools as well as money to implement state standards, testing, and “report card” comparisons of school districts, individual schools, and even students. Education policy analyst David Conley notes that, given current state policies in accountability and assessment, principals have become as responsible to the state government as they are to the local superintendent and board of education. School superintendents have been called on to support and facilitate improvements on a school-by-school basis, and in many states, local principals have been freed to make major decisions about how they are to meet measurable goals, creating a kind of “bottoms up meets top down” partnership style of educational management. (17)

In the recent wave of reform, Kentucky overhauled its public education system with echoes of the Progressive Era. In the 1980s, a coalition of business leaders and social reformers criticized the Kentucky system of education for politicized hirings and firings by locally powerful yet poorly trained school boards. The Prichard Committee on Academic Excellence (named after a crusading education reformer) culminated in a dramatic decision by the Kentucky Supreme Court that rejected the existing education finance system, and in 1990 the legislature passed the Kentucky Education Reform Act. (18)

The work of the blue-ribbon Prichard Committee, which included four former governors, generated widespread media attention and had strong financial support from Kentucky’s leading companies. The 1990 reform legislation increased funding for poor school districts, replaced an elective with an appointed chief state school officer, required extensive statewide testing, created local school councils that took power away from traditional school boards, and created controversial family centers at school sites to provide day care as well as health and social services for new parents (p. 281).

Major foundations, such as Rockefeller, Ford, MacArthur, and Spencer, have played a big role in education reform. With more than $60 billion in assets, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is richer than many small nations. “Gates has so much money to spend,” says education professor Diane Ravitch, “they have the power to set the agenda” for education. As Gates gave grants for small schools, “almost every district lined up to seek their money and to split up their high schools into small schools.” (19) Other foundations have included education reform among their funding program areas.

Problems occur, however, when such foundation grants expire. For instance, the Gates Foundation gave grants of $100,000 to 50 new, small New York City public schools. After these grants expired in 2006, one school executive asked, “What happens to that success when there is no more private money?” (20) Often, school districts must either take money from other programs to sustain an initiative or discontinue it. Another option is for schools to be run by private education corporations like the Edison Schools, a for-profit company that in 2006 managed 20 schools in Philadelphia and others across the country (p. 282).

Simpson, D., Nowlan, J. D., & O’Shaughnessy, B (2011). The struggle for power and influence in cities and states. Boston, MA: Longman/Pearson.

DEMOGRAPHICS

There are 54 million students enrolled in public and private schools in the U.S. An additional 1.5 million homeschoolers constitute 3% of the market. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) projects steady growth in enrollments to 57.9 million students in 2020. During this time, private school enrollments will decline slightly.

The teacher population has grown from 3.0M in 1995 to 3.7M in 2008 and is projected to grow to 3.9 million in 2020. The Department of Education projects more than a million new teachers will be needed in the next eight years because growth is occurring at the same time as the baby boomer component of the teaching profession is retiring. This demographic dilemma presents an opportunity for companies engaged in teacher professional development.

Public school students make up 86% of the school and homeschool population, and public school teachers are 89% of all teachers

Public and Private school enrollments and teacher population

Public Private Total

Schools 99,000 33,000 132,000

Students 48,023,000 5,488,000 53,511,000

Teachers 3,210,000 437,000 3,647,000

Staff 6,355,000 779,000 7,134,000

Homeschoolers 1,500,000

DISTRICTS

Of the 13,600 districts nationwide, the largest 26 claim 12.3% of the students, and the largest 6.4% (874 districts) have 53.5% of the students. The remaining 93.6% of the districts contain only 47% of the students. Two-thirds of the districts in the country have fewer than 2,500 students enrolled.

There are 874 districts with at least 10,000 students. Nationally, 6.4% of public school districts have 53% of the students. California currently has 1,025 school districts (343 unified; 526 Elementary; 77 high school; and 79 other).

Student Population in Districts with More Than 10,000 Students

Districts Students

Districts Size # of % of # of (millions) % of

100,000 or more 2 60.2% 5.9 12%

50,000 to 99,999 61 0.4% 4.2 9%

25,000 to 29,999 193 1.4% 6.6 14%

10,000 to 24,999 594 4.4% 9.0 19%

Total 874 6.4% Total 54%

Notes

- These figures are from the National Education Association and the U.S. Department of Education as reported in Sourcebook 2005, a publication of Governing magazine (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2005).

- S. Census Bureau, 2002; U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2003; and the U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2003.

- From the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2003, as reported in Dennis Patrick Leyden, Adequacy, Accountability, and the Future of Public Education Funding New York: Springer, 2005), chap.

- Kern Alexander and Richard G. Salmon, Public School Finance (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1995), 7—8.

- David Nasaw, Schooled to Order: A Social History of Public Schooling in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 30.

- Higher Education Resource Hub, “Land Grant Act: Histories and Institutions,” lune 18, 2007, www.higher-ed.org.

- Alexander and Salmon, Public School Finance, 10.

- Nasaw, Schooled to Order, I09, 120.

- Leyden, Adequacy, Accountability, and the Future of Public Education Funding, 4.

- Figures are from U.S. government sources as reported in Leyden, Adequacy, Accountability, and the Future of Public Education Funding, 6; and National Center for Education Statistics as reported in Kathleen O’Leary Morgan and Scott Morgan, eds., State Rankings 2006 (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2006).

- The Book of the States 2006 (Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments, 2006).

- Diane Ravitch, ed., Debating the Future of American Education (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1995), 3.

- Frederick Wirt and Michael Kirst, Schools in Conflict: The Politics of Education, 2nd ed. (Berkeley, CA: McCutchan, 1989).

- David T. Conley, Who Governs Our Schools: Changing Roles and Responsibilities (New York: Teachers College Press, 2003), 7.

- Conley, Who Governs Our Schools, 37.

- Education State Rankings, 2005-2006 (Lawrence, KS: Morgan Quitno, 2005).

- Conley, Who Governs Our Schools, 13, 57.

- For more extensive discussion of the Kentucky reforms, see Samuel Mitchell, Tidal Waves of School Reform (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1996), chap. 4.

- Karen W. Arenson, “Educators React to Shift in Leadership at Gates Foundation,” New York Times, November 4, 2006.

- Arenson, “Educators React to Shift in Leadership.”

Recent Comments